How maritime ports can advance industrial climate tech solutions

In Episode 4 of Voices in Tech, we hear from Max Harris, group head of strategy and sustainability at Associated British Ports, about the role ports can play in advancing the industrial energy transition, and PwC’s Shreekumar Rakshit weighs in on the state of climate tech investment. Listen to the audio.

Listen to “How maritime ports can advance industrial climate tech solutions”

Max Harris, group head of strategy and sustainability at Associated British Ports, talks about how technology is driving the energy transition at ABP, and PwC’s Shreekumar Rakshit shares his insights on climate tech investment and decarbonization for industrials.

About Voices in Tech

Hosted by series executive producer Shana Ting Lipton of PwC, Voices in Tech brings emerging tech to life through the stories of the companies solving big business problems at the intersection of technological acceleration and human innovation.

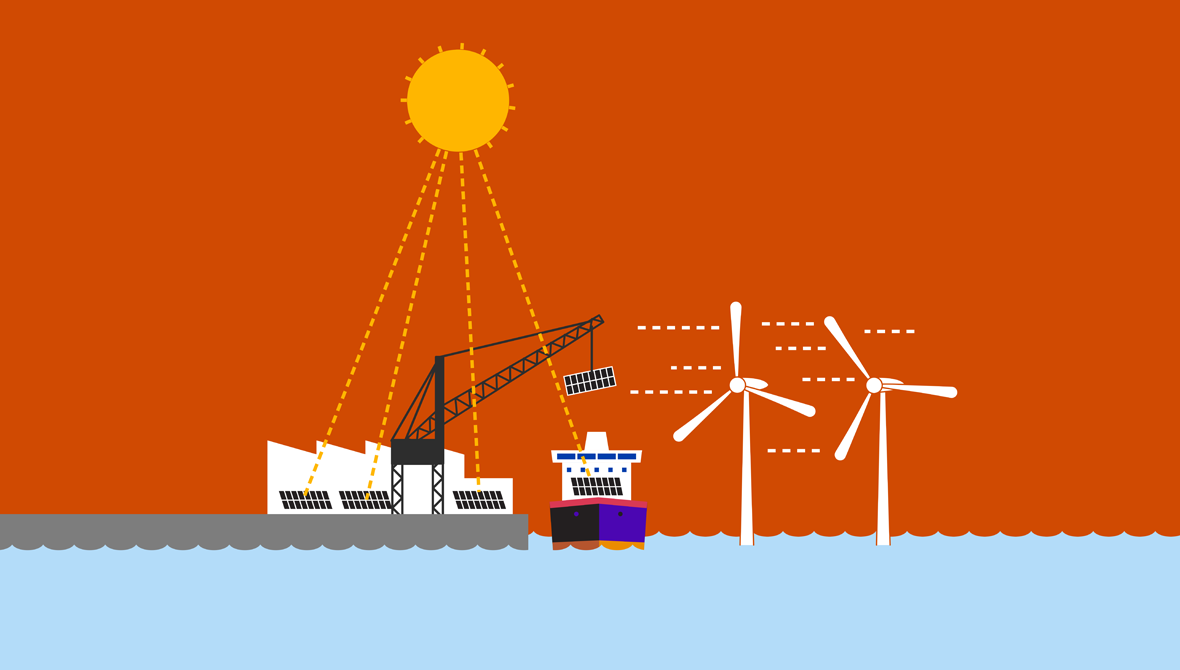

Decarbonizing heavy industries is challenging. It requires innovative climate tech, capital investment, and scale to succeed. Ports—which sit at the heart of large industrial clusters—may be primed to help. With vast land assets in strategic locations, they can support technologies like onshore wind turbines and carbon capture and storage.

Associated British Ports (ABP), the UK’s largest ports operator, sees itself as a leader in the industrial energy transition. Its group head of strategy and sustainability, Max Harris, discusses how the company is leveraging its infrastructure and relationships with its customers in hard-to-abate industries to help tackle their decarbonization challenges—serving as a hub for climate tech pilot initiatives and manufacturing.

ABP’s new accelerator program is connecting industrial customers and start-ups that are ready to scale up in order to solve big energy transition challenges through hard tech solutions. PwC’s Shreekumar Rakshit adds his insights on investment trends, drawing from PwC’s State of Climate Tech 2024 report.

Guest: Max Harris, Group Head of Strategy and Sustainability, Associated British Ports

Featuring: Shreekumar Rakshit, Strategy& advisor, director, PwC UK

Max Harris: We’re looking to bring together the big industrial players in the local context of our ports, together with the really innovative, talented start-ups that are looking to scale and apply their great technology to real-world industrial challenges.

Shana Ting Lipton: That’s Max Harris. And today, we hear the story of how his company, the UK’s largest ports operator, Associated British Ports, is using its infrastructure and convening powerful industrial players to bring climate tech start-ups to its shores—helping its customers solve some of the biggest energy transition challenges.

I’m your host, Shana Ting Lipton, with PwC, and this is Voices in Tech, from our management publication, strategy+business, bringing you stories from the intersection of technological acceleration and human innovation.

It’s been more than three years since investments in global climate tech peaked, back in 2021. And, as you’d probably expect, start-ups trying to address some of the biggest challenges in the hard-to-abate industrial space are finding it more difficult to raise capital. The industrials sector—which includes steel manufacturers and cement producers—is responsible for 34% of global greenhouse gas emissions. But the falloff in funding over the past few years has been steep: investments in companies working on industrial climate tech fell from US$12 billion in 2023 to US$3 billion in 2024—a 75% drop—according to PwC’s State of Climate Tech 2024. The imperative to find solutions in this area is stronger than ever. One answer comes from an unlikely 21st-century innovation driver: maritime ports. Here’s Shreekumar Rakshit, a director with PwC UK who works as an advisor with the firm’s Strategy& consulting business.

Shreekumar Rakshit: Ports are critical parts of our global economic system, right? Eighty percent of the merchandise flows through sea routes, where the port plays a pivotal role. Now, energy transition brings both opportunities and challenges for the ports.

One of the major challenges for them will be how to handle the declining volume of carbon-intensive raw materials or energy carriers, like crude oil or metallurgical coal, which are currently used in steelmaking. At the same time, they may also face the challenges to decarbonize their own operation, which means investments into solar energy, electrification of their vehicles, or handling equipment and changing the way they operate today, which means investment and changes in their processes.

In terms of opportunity, I see that ports actually can work as an energy hub—a green energy hub. For example, ports have got a lot of unused land, which they can use to build renewable energy projects. So, to offset the declining volume of, let’s say, carbon-intensive material, they need to find out alternative sources of revenues—whether to develop the biofuel refinery or renewable energy hub on their land, which can actually help them offset their revenue losses, which means that they actually invest in some of these interesting innovative technologies.

Lipton: Private ports operator Associated British Ports, or ABP, has a network of 21 ports, which facilitate £40 billion a year in exports from the UK. Max Harris, group head of strategy and sustainability at ABP:

Harris: ABP is the largest port owner and operator in the UK. We’re a privately held business owned by three pension funds and two sovereign wealth funds. We support all kinds of different sectors—from heavy industrial businesses, like steelworks and oil refineries and power generation plants, but also clean energy companies, like offshore wind and hydrogen and carbon capture and storage. We have two main business models. On the one hand, we’re a big landowner—so we support other businesses to come in and operate terminals at our ports. And on the other hand, sometimes ABP operates the terminals ourselves.

Lipton: Some of ABP’s traditional ports customers, like shipping and logistics companies, face a confluence of escalating risks. Think about how supply chains have been disrupted by one crisis after another over the past few years. But one force stands out.

Harris: ABP is grappling with the same macrotrends that every other business around the world is grappling with, such as climate change, geopolitical shocks, pandemics, and the rise of AI and automation. The one that really impacts us is climate change. There’s increasing sea levels, which fairly obviously affect ports—we’re never going to move our locations away from the coast. But then on the other side of risk is clearly opportunity. ABP’s ports are located right at the heart of major industrial clusters around the UK, where greenhouse gas emissions are pretty high. And so, everybody recognizes that the big challenge is how to reduce those emissions whilst also maintaining sustainable, profitable business.

Lipton: But emissions in the industrials sector are famously hard to abate. Increased use of renewables alone may not be enough to mitigate CO2 emissions. Some players are looking to the development of fuels like hydrogen. And to technologies like point-source carbon capture and storage, which generally require a lot of land for storage and pipelines to transport captured CO2. Harris believes ABP is in a unique position to work with its customers to develop such projects.

Harris: As we move into the energy transition, the role of ports is ever more important. So, you can’t do offshore wind installation, manufacturing, without ports. You can’t have hydrogen imports, and hydrogen production, green hydrogen, or clean hydrogen at scale without ports. You can’t do carbon capture without ports. So, our role has never been more critical. And so, we help to bring together large energy producers, large transport providers, like shipping lines, like trucking companies. And we also bring together the large industrial process owners—so, oil refineries, cement works, and others.

Lipton: This new role for ports starts with ABP’s own net-zero target of 2040, which it’s backed with a £600 million investment in decarbonizing its operations. This sustainability strategy overlaps with the ports operator’s business strategy, which involves a rethink of how it uses its 8,600-acre portfolio of land.

Harris: We engage with lots of different tech companies, and they often see ports as an amazing place to test their technology. At the Port of Southampton, we worked with Verizon to deploy the first private 5G network on an industrial site in the UK. And so, that’s really focused on industrial IOT use cases. And one great example of that is how we work with our automotive customers who are bringing vehicles into the UK market. And so, with better 5G connectivity, we can use our terminal operating systems to optimize the path of the vehicles from the ship to the storage location based on either time, cost, and now carbon. So, having better 5G connectivity really makes a difference to not only supply chain cost reduction but also to CO2 reduction.

We’re supporting the growth of a whole new industry, in terms of floating offshore wind, and this is where the wind turbines, instead of being fixed to the seabed, they’re actually floating, and they’re just tethered with some wires to the seabed. And so, you have a semi-submersible structure sitting in the water that is the size of a football field—either made of steel and/or concrete—and then you have a wind turbine that’s the size of the Eiffel Tower or even larger sitting on top. Remember, these are floating structures. So, this is a huge engineering challenge. And this industry doesn’t really exist at any scale today. So, our location in Port Talbot is perfect to access wind resources in the Celtic Sea, in between the UK and Ireland, and our ports are going to host the manufacturing of these floating structures, which are absolutely enormous structures, and then they’ll be floated very slowly out to the location in the Celtic Sea. Location is really important, because you can’t make these things in Southeast Asia and then float them across the world, because they’re too large, and they’re not stable enough to be floated at such slow speed all across the world, given the weather windows.

Lipton: Harris and his colleagues are also thinking about how to draw more climate tech innovation to their ports and ways to invest in today’s young companies that could, in the future, grow into more established customers.

Harris: So, ABP’s typical customer would sign up to long-term contracts—so, 10-, 15-, sometimes 50-year contracts—whereas start-ups are just not in a position to sign up to those kind of long-term contracts. So, we need to partner with them in a different way. And so, the way that we’re looking to do it is through housing their proofs of concept, their pilot projects to test their technology, on the one hand, and then all the way up to providing discounted leases, for example, in exchange for a slice of their equity.

The Energy Ventures Accelerator is an initial 12-month project to identify the highest potential energy transition start-ups in the hardware space. So, we’re not focused on software. This is all about hard tech. And so, we’re looking to attract the best and brightest to come to our ports to leverage our land assets and our infrastructure assets, and also to meet our customer base and meet the local stakeholders—local government, local councils, local enterprise partnerships, etc.

Lipton: ABP brought in Silicon Valley VC platform Plug and Play—with its network of 60,000 start-ups—as a collaborator, and set off strategically to attract innovative companies at a particular level of maturity.

Harris: So, we’re looking to form partnerships with start-ups from between the seed rounds, but, really, the sweet spot for us is around Series B, when start-ups are at that inflection point between start-up, proving the technology, and then moving into the scale-up phase. So, really looking to grow their manufacturing base.

So, what ABP offers is a land location and access to our commercial ecosystem, so that they can not only scale their manufacturing, so they have more product to sell, but also give them access to the right potential customers, so that they can then sell that product and identify the key off-takers and customers of the future.

Lipton: This type of corporate venture is in line with what PwC’s Rakshit is now seeing in the industrial decarbonization space.

Rakshit: Some of these large corporates, they are trying to innovate on the capital stack, right? Because hardware-based climate technology companies require a lot of money, for example, for a demonstration project they may need US$100 million–plus, and if it is a first-of-a-kind industrial plant, it may mean US$300 to US$500 million. Since these technologies are not proven, you cannot bring, let’s say, traditional investors. As a result, they try to work as a catalyst to bring different forms of capital—whether it’s government money, whether it’s, let’s say, catalytic capital like [from sustainability organization] Breakthrough Energy, who take more risk on this type of technology. And with the involvement of a corporate, it makes it easier for start-ups to get access to different types of capital, and following a blended finance approach, which is important.

Lipton: The preference for more mature start-ups and scale-ups as Max Harris mentioned aligns with PwC’s State of Climate Tech 2024 findings. In 2024, 61% of corporate climate tech deals were middle- or late-stage deals.

Rakshit: Overall, in the climate tech investment space, what we are seeing is that the hype is gone now, and investors are more disciplined and focused. They are not going to invest in any mediocre tech solutions. They are targeting really robust technology and solutions. In the industrial decarbonization space, the trend is still similar, like we have seen in the earlier years. This is still not attracting as much investment like other sectors, like e-mobility and renewable power. And understandably, because these technologies are still not at a mature level to give investors the confidence and, let’s say, hydrogen electrolysis, carbon-capture storage or long-duration energy storage. Generally, to deploy this technology, you need to bring in massive physical changes, engineering. That means we are trying to change something which has been built over 150 years in our industrial system and energy system, right? That’s not easy. You need enormous amounts of capital and resources both from people and a financial perspective.

Lipton: Harris and his colleagues are hoping their accelerator can provide a platform for addressing these types of industrial reconfiguration challenges.

Harris: So, as part of the Energy Ventures Accelerator, we’re looking to host a series of events that bring together the start-up community around the energy transition and also big corporate partners of ABP’s, together with the public sector and other local stakeholders around our ports. And so, the idea is to really match-make best-in-class new technologies with real-world industrial transport and energy challenges that our current customers are facing.

We hosted an event back in November, in Hull. So, really bringing together the Humber [UK] industrial ecosystem—so big energy providers, big industrial process owners, and then shipping customers, together with great start-ups in hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, energy storage, and offshore wind.

It’s not like Dragons’ Den. It’s not like Shark Tank. We’re not trying to gamify the experience. We’re looking to bring together the big industrial players in the local context of our ports, together with the really innovative, talented start-ups that are looking to scale and apply their great technology to real-world industrial challenges.

Lipton: One of those challenges is readying the industrial ecosystem to deploy climate technologies.

Rakshit: Overall, I think I’m positive about the direction of the energy transition and decarbonization. There is no going back on that. Ports can play a big role in terms of, let’s say, carbon capture and storage technology deployment. The point is that the port will not be ready to invest in such an infrastructure if the whole ecosystem is not ready. The industrial user who would like to use the carbon capture technology—they should be ready to deploy that technology at scale, because ports will need huge amounts of volume to flow to make an investment for a captured carbon transport hub. And it’s not going to happen in a short period of time. So that means that they need experimentation, partnership-building.

Harris: We’re really leaning into one of the most difficult challenges that is faced across the whole investment landscape globally: is how to get climate tech solutions to scale and to be economically attractive to deploy. And then, secondly, how to retain talent within the UK market and how to, on the other, on the flip side, how to attract overseas talent into the UK market. And so, we’re hopeful that ports as a key nexus of talent, infrastructure, and technology can be the landing spot—you know, the launchpad for these new energy transition technologies that will transform our future.

Lipton: Thanks for listening, and stay tuned for more episodes of Voices in Tech, brought to you by PwC’s strategy+business. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity.